PHI 030: May 4, 2015

Table of Contents

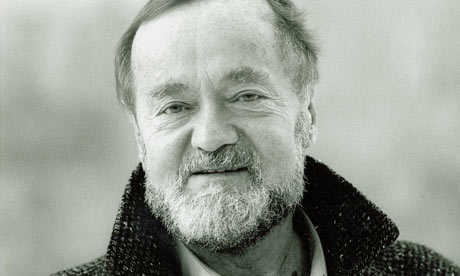

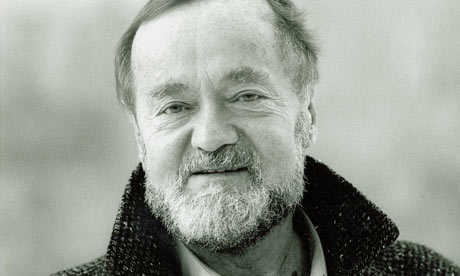

''Do Sub-Microscopic Entities Exist?'' by Stephen Toulmin (1922-2009)

Key Ideas

Select Quotations

A Short History of Cloud Chambers

Charles Thomson Rees Wilson (1869 - 1959)

''Do Sub-Microscopic Entities Exist?'' by Stephen Toulmin (1922-2009)

Obituary in the Guardian

Key Ideas

- It isn't clear, even to scientists, whether unobservables exist because we are not precise enough about what 'exist' means (1, 2, 3, 4)

- 'Exist' can be used in at least three ways. Meaning:

- Used to exist, but no longer does, e.g., dodos (4)

- Exists in imagination as opposed to reality, e.g., Ruritania (4)

- Exists in the sense of l lines on a map (4)

- The question of sub-microscopic entities should be thought of in terms of C. (6, 7, 8, 9)

- Asking whether they exist "acts as an invitation" to produce one, but this is very difficult (10, 11)

- Some such entities can never be produced (12, 13)

- We should only give up on such entities if they cease to be explanatory (14)

- Scientific theories are often adopted prior to our having evidence that the terms for the sub-microscopic entities name real objects (15, 16, 17)

- Just because scientists use terms for sub-microscopic entities does not mean that they believe they exist (17, 18, 19)

Select Quotations

- Nonscientists are often puzzled to know whether the electrons, genes, and other entities scientists talk about are to be thought of as really existing or not. Scientists themselves also have some difficulty in saying exactly where they stand on this issue. Some are inclined to insist that all these things are just as real, and exist in the same sense as tables and chairs and omnibuses. But others feel a certain embarrassment about them, and hesitate to go so far.

- Yet the theory of electrons does explain electrical phenomena in a way in which no mere translation into jargon, like "pyrexia" can explain a sick man's temperature; and how, we may ask, could the electron theory work at all if, after all, electrons did not really exist?

- Stated in this way, the problem is confused: let us therefore scrutinize the question itself a little more carefully. For when we compare Robinson Crusoe's discovery with the physicist's one, it is not only the sorts of discovery which are different in the two cases. To talk of existence in both cases involves quite as much of a shift, and by passing too swiftly from one use of the word to the other we may make the problem unnecessarily hard for ourselves.

- If we ask whether dodos exist or not, i.e., whether there are any dodos left nowadays, we are asking whether the species has survived or is extinct. But when we ask whether electrons exist or not, we certainly do not have in mind the possibility that they may have become extinct: if we ask whether Ruritania exists, i.e., whether there is such a country as Ruritania, we are asking whether there really is such a country as Ruritania or whether it is an imaginary, and so a nonexistent country. But we are not interested in asking of electrons whether they are genuine instances of a familiar sort of thing or nonexistent ones:

- In each case, the word "exist" is used to make a slightly different point, and to mark a slightly different distinction.

- A more revealing analogy than dodos or Ruritania is to be found in the question, "Do contours exist?"

- If he asked his question in bare words, "Do contours exist?" one could hardly answer him immediately: clearly the only answer one can give to this question is "Yes and No." They "exist" all right, but do they exist? It all depends on your manner of speaking.

- The real question was: "Is there anything to show for contours-anything tours — anything visible on the terrain, like the white lines on a tennis court? Or are they only cartographical devices, having no geographical counterparts?"

- This is very much the sense in which the term "exists" is used of atoms, genes, electrons, fields, and other theoretical entities in the physical sciences.

- To a working physicist, the question "Do neutrinos exist?" acts as an invitation to "produce a neutrino," preferably by making it visible. If one could do this one would indeed have something to show for the term "neutrino," and the difficulty culty of doing it is what explains the peculiar difficulty of the problem. For the problem arises acutely only when we start asking about the existence of submicroscopic entities, i.e., things which by all normal standards are invisible.

- Our problem is accordingly complicated by the need to decide what is to count as "producing" a neutrino, a field, or a gene.

- If one could not show, visibly, that neutrinos existed, would that necessarily be the end of them? Not at all.

- Not all those theoretical entities which cannot be shown to exist need be held to be nonexistent: there is for them a middle way.

- Even if we had reason to believe that no such demonstration ever could be given, it would be too much to conclude that the entity was nonexistent; for this conclusion would give the impression of discrediting something that, as a fertile explanatory concept, did not necessarily deserve to be discredited. To do so would be like refusing to take any notice of contour lines because there were no visible marks corresponding responding to them for us to point to on the ground. The conclusion that the notion must be dropped would be justified only if, like "phlogiston," "caloric fluid," and the "ether," it had also lost all explanatory fertility.

- A scientific theory is often accepted and in circulation for a long time, and may have to advance for quite a long way, before the question of the real existence of the entities appearing in it can even be posed.

- So, paradoxically, one finds that the major triumphs of the atomic theory were achieved at a time when even the greatest scientist could regard the idea of atoms as hardly more than a useful fiction, and that atoms were definitely shown to exist only at a time when the classical atomic theory was beginning to lose its position as the basic picture of the constitution of matter.

- Evidently, then, it is a mistake to put questions about the reality or existence of theoretical entities too much in the center of the picture. In accepting a theory scientists need not, to begin with, answer these questions either way: certainly they do not, as Kneale suggests, commit themselves thereby to a belief in the existence of all the things in terms of which the theory is expressed.

- Having noticed that a theory may be accepted long before visual demonstrations can be produced of the existence of the entities involved, we may be tempted to conclude that such things as cloud-chamber photographs are rather overrated: rated: in fact, that they only seem to bring us nearer to the things of which the physicist speaks as a result of mere illusion.

- But this is still to confuse two different questions, which may be totally independent: the question of the acceptability of the theories and the question of the reality of the theoretical entities.

A Short History of Cloud Chambers

Charles Thomson Rees Wilson (1869 - 1959)

In 1911 C. T. R. Wilson was studying clouds by "tramping regularly to the summit of Ben Nevis, a famously damp Scottish mountain," when it occurred to him to create an artificial cloud chamber in which air is cooled and moistened.

"When he accelerated an alpha particle [which is a positively charged particle that consists of two protons and two neutrons bound together] through the chamber to seed his make-believe clouds, it left a visible trail — like the contrails of a passing airliner" (from A Short History of Nearly Everything by Bill Bryson)

"The general procedure was to allow water to evaporate in an enclosed container to the point of saturation and then lower the pressure, producing a super-saturated volume of air. Then the passage of a charged particle would condense the vapor into tiny droplets, producing a visible trail marking the particle's path" (from Hyperphysics)